The Sound Of Philadelphia

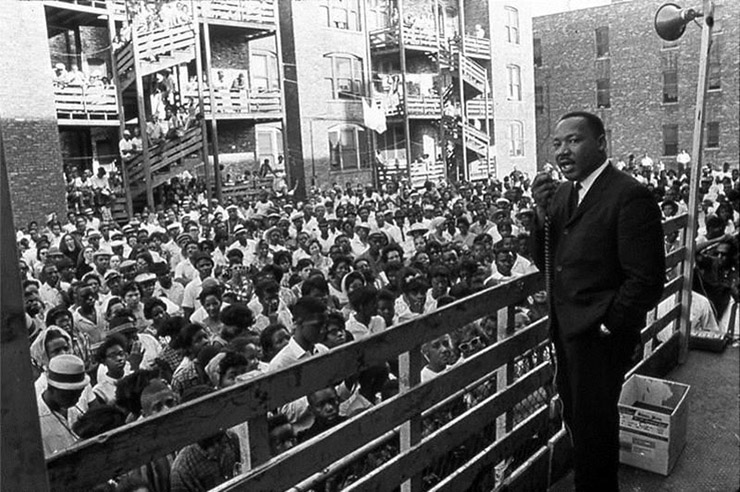

The former Philadelphia International Records Building

Just as Motown and STAX were closely associated with a specific sound from a specific city (Detroit and Memphis) in the 1960s and early 1970s, Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff created “The Sound Of Philadelphia” in the 1970s, catapulting Philadelphia International Records (PIR) to worldwide fame.

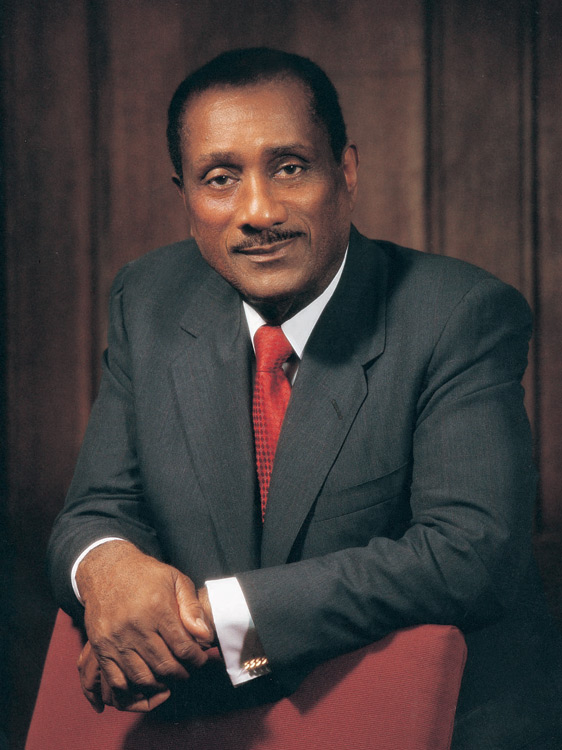

Kenneth Gamble (born 1943 in Philadelphia) was a background singer and lyricist who first met Leon Huff (born 1942 in Camden, NJ) in 1962 at Philadelphia’s Shubert Theatre. They complimented each other as songwriter and pianist. Eventually, Gamble and Huff became members of a local band, the Romeos, along with Thom Bell, who later became a famous songwriter and producer.

Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff collaborated on a number of earlier R&B songs, but the pop hits did not arrive until 1966 with the Intruders and Soul Survivors’ We’ll Be United, Together, Cowboys To Girls, and Expressway To Your Heart among others. They also wrote and produced Atlantic hits for Archie Bell & the Drells and Wilson Pickett. But most of all, they were instrumental in reviving the career of ex-VeeJay singer, Jerry Butler in 1967 with hits like Only The Strong Survive, What’s The Use Of Breaking Up and Hey Western Union Man on the Mercury record label.

Kenny Gamble & Leon Huff

These Jerry Butler records really set the scene for what was to come: silk voices singing in high register, a tight rhythm section and lush string arrangements. Gamble got the entrepreneurial bug and started his own record company in 1967, but it folded due to distribution and collection issues common to small record labels. He next tried his hand co-founding Neptune Records with Huff in 1969. Wiser from the first experience he signed a national distribution deal with Chess Records.

In 1969, the Neptune label was founded and distributed through Chess Records. Although Neptune released only 4 albums, it marked the starting point for Gamble and Huff’s collaboration. Upon recommendation by the Intruders, they also brought in the O’Jays. And in 1970, Thom Bell joined the label as an arranger, writer, producer and musician. By 1971, Chess Records’ involvement with Soul Music declined, so Gamble and Huff signed a national distribution, music catalog and financial deal with CBS Records, then changed the company name to Philadelphia International Records (PIR). Though no longer an independent record label, with distribution and financial issues behind them, PIR was free to go in the positive message artistic directions it desired.

What elements lead to the creation of their musical signature? Gamble and Huff learned that a successful record label needed a strong cache of writers, musicians, arrangers and producers to maintain a stream of hits. They had the brilliance and luck to hire Gene McFadden and John Whitehead as associate producers and arrangers. Linda Creed joined Thom Bell to form a high-impact Soul Music writing, arranging and producing tandem at the company. Next, Gamble and Huff constructed a house band from accomplished session artists. In keeping with their mission statement to deliver positive messages, they called their session band, Mother Father Sister Brother (MFSB) comprised of Roland Chambers and Norman Harris (guitars), Vince Montana (vibes), Ronnie Baker (bass) and Earl Young (drums).

In the 1970s, Gamble and Huff puzzled together dance rhythms, orchestral arrangements, and positive topical lyrics that established a musical signature having sophisticated soulful orchestration. It was lovingly called, The Sound Of Philadelphia. Recording most of The Sound Of Philadelphia at the Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia, PIR was finally prepared for lift-off.

The O’Jays finally hit it big in 1972 with Back Stabbers. The O’Jays continued rolling out the hits with Love Train, For the Love of Money in the 1970s. Other prominent acts on the PIR label were Billy Paul (Me and Mrs Jones) and Harold Melvin And The Blue Notes (If You Don’t Know Me By Now and The Love I Lost), Blue Magic, Jean Carn, The Spinners (Could it Be That I’m Falling in Love), Stylistics (Betcha by Golly, Wow). The Three Degrees, and Delfonics (Didn’t I Blow Your Mind This Time). PIR were causing Philadelphia ticket agencies to go crazy with business with hit after hit. Philadelphia International Records became a force in the Soul Music market and even drew praise from its rivals.

As PIR rolled out the hits, STAX Records imploded and Motown’s record identity tarnished a bit after moving from Detroit to LA. Soon it became easier for PIR to attract top artists like The Jacksons, Jerry Butler, Lou Rawls and Phyllis Hyman. They nearly signed the Temptations after they left Motown in 1976.

Able to anticipate market trends, PIR helped create the disco craze when it introduced The Hustle by Van McCoy in 1974. They also had good karma. Producer and songwriter Richard Barrett is credited with bringing the Three Degrees to PIR in 1973. A short time later, Don Cornelius, producer and host of Soul Train asked the Three Degrees to do vocals for the show’s new theme track, with instrumentals by MFSB. Thus, The Sound Of Philadelphia became a huge disco hit in 1974 and known the world over as Soul Train’s theme song.

Storm clouds came their way in 1975. Charges were brought against Huff for offering Payola in exchange for airplay. The charges were dropped in 1976, but Gamble was fined $2,500 in related matters, which tarnished the record company’s reputation. It’s unclear why they were singled out, particularly since Payola, often non-monetary, was common in the industry. Then in 1982, mega-star sex symbol Teddy Pendergrass smashed his car into a highway divider, paralyzing him from the waist down and body slamming his recording career.

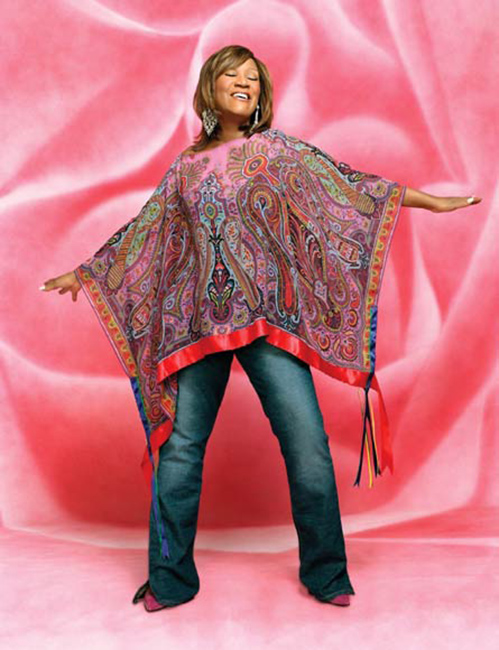

Patti Labelle

In 1983, there was a bit of good news for The Sound Of Philadelphia. Patti LaBelle released the I’m In Love Again album and it reached gold sales status. Unfortunately, it was the last PIR album to reach gold. By 1985, the hits ebbed and Philadelphia International Records switched its distribution to Manhattan (a Capitol subsidiary). Still struggling to get more radio airtime, publicity and record store shelf space, they switched to BMG in 1991 — again without much success. The 1990s were not kind to most record labels, so no one should be surprised at the difficulties PIR encountered.

The prominence of PIR was usurped by a new generation of record labels. Nevertheless, PIR set benchmarks for community relations and style as Gamble & Huff maintained a Philadelphia record label rather than move to LA or New York. Gamble-Huff Music, the successor company to PIR, has a well-earned place on Philadelphia’s Avenue of the Arts and Philly loves them back. One example of that love is, renowned Philadanco Dance Company presented a work set to the vintage music from Philadelphia International Records.

Though the historic Philadelphia International Records building at 309 South Broad Street was torn down in 2015, The Sound Of Philadelphia lives on. For more about their triumphs and tribulations of Philadelphia International Records, visit http://www.gamble-huffmusic.com and Http://www.soul-patrol.com.