Bstrong>Bust of Jean-Baptiste Pointe DuSable bust, the founder of Chicago; (c) Soul Of America

Chicago History

In the area they called “Chicakgou” Pottawattomie Indians, who nomadically passed through the region, recorded the first settler as Jean Baptiste Pointe du Sable. Du Sable, an African-French trader, came to the region in 1790 to establish the first businesses, which of course leveraged his trading talents and others he acquired. A successful businessman, Du Sable employed many people of different races on the banks of the Chicago River. So in both a historic and practical sense, Du Sable was clearly the Father of Chicago.

In the early 1800s, Chicago became an important Midwest commercial center and a way station for African-Americans who fled slavery. Illinois Black Codes constrained the movement of all African-Americans, making it particularly hard for people using the Underground Railroad to Wisconsin and Canada. These codes were so effective at the beginning of the civil war, that Chicago’s Black Population was only 1,000.

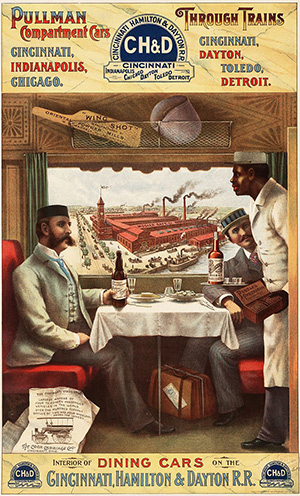

1894 poster, Pullman Porter serving dining car

Owners in the meatpacking, grain processing, oil processing and heavy metal industries made great fortunes. Jobs, though numerous, were often cyclical. Excluding the great recessions, the economic balance was maintained by one industry peaking as another industry cut back. Heeding the call for continuous work, all walks of life migrated here from 1870-1930, thus building another Chicago nickname, “The City That Works.” The most dependable form of work for black men was to be a Pullman Porter on the many trains to and from Chicago Union Station.

The great journalist Ida B. Wells moved to the city after being run out of Memphis for reporting on Blacks being lynched. She was followed by scores of African Americans escaping the South’s orgy of violence. By 1910, Black Population in Chicago totaled 40,000. By 1920, it swelled to 80,000. African-American migrants settled on the Southside of the city in a section called the Black Belt. A smaller black community sprouted up on the Westside.

African-Americans did not escape oppression from Southern bigotry. It is well documented that they were last hired in boom times, and first fired during business contractions. At the same time, less qualified European immigrants were admitted, quickly trained on jobs, and rapidly promoted. Even in boom times, qualified African-Americans were limited to the worst/most dangerous positions in trade and labor unions.

Sadly, many African-Americans were only hired when industrialists needed them to break strikes. Such practices created a climate of enmity and distrust by Anglo-Americans toward Africans-Americans. Outside of work, it increased housing segregation that severed interracial communication. Despite strikebreaker practices hated by all, African-Americans maintained enough menial labor jobs in the factories to support small businesses in two growing black communities.

The U.S. Department of Defense was uneasy about training large numbers of African-Americans with weaponry, so many who volunteered were not permitted to serve. Most African-Americans fortunate enough to serve did so honorably and with valor in World War I. Those who stayed behind found many jobs that would normally be inaccessible. When WWI ended in 1918, Chicago had a large number of Anglo-American veterans expecting to reclaim the same jobs, while African-American vets hoped more middle-income jobs would open to them.

Many Anglo-American veterans were jealous of African-American economic accomplishments in their absence. When it took longer than expected to absorb Anglo-American veterans in the workforce, they demanded that Black workers be fired or laid off. Such was the powder keg behind the Chicago Race Riot of 1919.

The fuse was lit under highly questionable circumstances. A handful of Anglo-Americans made up or exaggerated charges against a single African-American at a downtown establishment. Events escalated to form a large mob that set to harm all black people and their property. The police did little to stop it. By the time white mobs finished their destruction, 38 African-Americans were killed and most Southside businesses, excluding those run by organized crime, were burned and looted.

Perhaps it was Chicago’s resolute sense of defiance against racism that attracted droves of African-Americans to continue migrating here. In 1928, Oscar de Priest became the first African-American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives since Reconstruction ended in 1877. By 1930, Chicago’s black population jumped to 240,000. Thus, the period between 1910 and 1930 became known as the “Great Northern Migration.”

The historic Chicago Bee Building

It was also an era for Southside gangsters who employed black performers at their Grand Terrace Ballroom – Chicago’s version of the Cotton Club. As the FBI reduced organized crime in the 1930s, black-owned businesses in the Overton Hygienic Building (Chicago Bee Building) and others along State Street enabled Bronzeville to function like a self-contained city. During this time, Bronzeville competed with Harlem for political, business, and cultural influence on the social consciousness of African-Americans.

During and after World War II, a second wave of African-Americans and Anglo-Americans moved to Chicago for jobs. Due to restrictive housing covenants, however, African-American migrants were constrained to the Southside and Westside, causing severe housing shortages in both areas. Rather than use legal and political leadership means to eliminate race-based job and housing discrimination, “White Guilt” caused political leaders to approve spirit-killing Welfare and build high-rise public housing in Chicago and elsewhere nationwide. In stark contrast, Anglo-American communities received home & business renovation loans, and public housing was severely limited.

The notorious Cabrini-Green Homes once housed 15,000 residents on the Near Northside. It was built in 1942 and demolished from 2000-2011. Given it was surrounded on three sides by old factories and middle-class and affluent districts, that site has been undergoing redevelopment since the early 2000s. By 2025, there will be a combination of single-family rowhouses, a shopping center, a redeveloped park and upscale high-rise buildings to create a mixed-income neighborhood.

Cabrini-Green Homes

The Godzilla of these projects was the 6-mile-long Robert Taylor Homes — largest contiguous public housing project in the nation. To the east, it faced Bronzeville. To the west, it faced I-90 Freeway, which was a physical and social barrier to Anglo-American communities in Southwest Chicago. A few years later, more high-rise public housing projects were built on the eastern side of Bronzeville. This sandwiching effect devastated a well-functioning community of:

• odd-job workers paid by cash

• minimum-wage workers

• middle-income workers & professionals

• small businesses

Robert Taylor Homes was intended for 11,000 residents but ultimately housed 27,000. The excessive warehousing of Welfare recipients, odd-job workers, minimum-wage workers and laid-off middle-income workers concentrated alcoholism, drug use, and gangs that triggered a middle-income flight from Bronzeville. Their exit crippled small businesses and achievement levels in schools. Though some people survived Robert Taylor Homes to live inspiring lives, that combination of factors ensured intergenerational poverty & despair for too many families. Even though Robert Taylor Homes were torn down between 1998-2007, it will take several decades to reproduce a well-functioning, mixed-income Bronzeville.

The city has been fortunate to have a cadre of respected black leaders trying to reverse a century of poor public policy. Chicago elected its first black mayor, Harold Washington, in 1983. Though he clearly had enemies, Washington was a respected politician by friends and foes alike, in part because he was never convicted of corruption. In 1987, Mayor Washington died of a heart attack while in office.

Based largely on her supportive Chicago base, Carol Mosley-Braun became the second African-American U.S. Senator in the 20th Century. Even a former Black Panther, Bobby Rush and a Soul Music balladeer, Jerry Butler, became publicly elected representatives. Of course, Barack Obama rose through the ranks to become the 2nd African-American U.S. Senator from Illinois and the first African-American President.

Chicago can boast that it once had three of the richest African Americans: Ebony and Jet magazines publisher John Johnson, Oprah Winfrey, and Michael Jordan. Before Michael Jordan, Walter Payton of the Bears stole the heart of Chicago sports fans. Michael, Oprah, and Walter once owned or had naming rights to popular Chicago restaurants at the same time. Of course, Reverend Jesse Jackson and Minister Louis Farrakhan also let their leadership presence be known.

Even though the region has many years ahead to reabsorb thousands of people from the Godzilla-like housing projects that were town down, entrepreneurial activity and sensible public works are yielding visible results in Bronzeville. Assuming black male employment improves and the pace of renovation increases, Bronzeville may experience a second Black Renaissance.