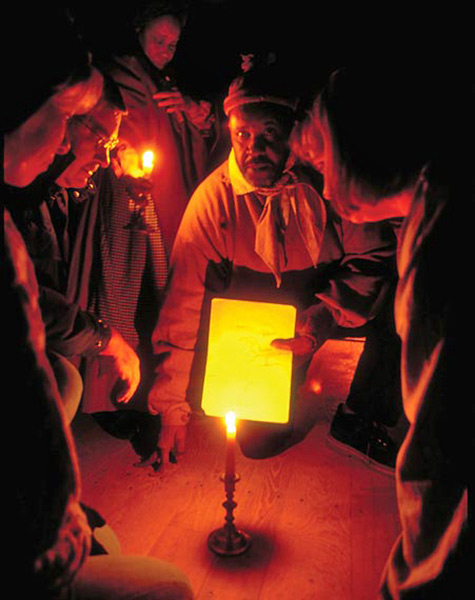

Follow the North Star storyteller at Conner Prairie; credit Visit Indy

Indianapolis History

In the years prior to the arrival of the white man, the Miami and Potawatomi Indians enjoyed the riverbanks and streams of the area. In quick succession, European Americans settled Indianapolis in 1820, chose it state capital in 1825, incorporated the city in 1832 and reincorporated in 1838.

African Americans arrived in 1836 when William Paul Quinn and Augustus Turner founded Bethel AME Church. The church, active in the anti-slavery movement, was a station for the Underground Railroad. While slavery was illegal in Indianapolis, there were many pro-slavery sympathizers, some employed by slave owners in Kentucky, a slave state next door. Allegedly, pro-slavery sympathizers torched the church in 1862.

In 1847, Indianapolis connected with a national railroad system, thereby expanding economic opportunity and fueling expansion of the city. Like European immigrants, free African Americans were attracted here for economic opportunity. German and Irish immigrants encountered less resistance to work in the labor trades, compared to African Americans. Multiplied over many decades, this grievous inequity established a disproportionately large Black underclass. Despite additional obstacles, African Americans created a vibrant community along Indiana Ave and West Street, which produced the nations first Black millionaire, Madame C.J. Walker.

Indy’s location in the middle of Indiana farmland has distribution advantages that attracted over sixty car manufacturers by 1910. But, Indianapolis never threatened Detroit’s auto supremacy because the absence of a navigable river prohibited efficient transportation of bulky materials, such as coal and iron, which are necessary to grow an auto industry. Nevertheless, Indy attracted a healthy share of major pharmaceutical companies, including Eli Lilly.

For a time, the automotive industry attracted African Americans from the South, but their arrival was not warmly greeted. To European Americans, more African Americans meant increasing competition for low wage jobs. Primarily in response to Indianapolis job competition, the state of Indiana quickly registered the most Ku Klux Klan members in the nation.

Fortunately, all was not doom and gloom for African-Americans. Until the Depression, Indy’s economy surged and there were plenty of cultural outlets for African Americans. A lively Jazz and Blues Music Tradition sprang up along Indiana Avenue, which was frequent stop on the Chitlin’ Circuit. Aside from its entertainment value, Walker Theatre became a beacon of Black pride and accomplishment. The Indianapolis ABC’s became a successful Negro Leagues Baseball team.

A second wave of black migration occurred during World War II, forever altering city composition. By the 1960’s Indianapolis was one of the most segregated cities in the USA. As fate would have it while on the presidential campaign trail, Robert F. Kennedy’s was speaking to a large crowd of African Americans on the eve of 4 April 1968. Most journalists and historians credit his calming speech and the support of Black leaders in attendance, as the primary reason Indianapolis avoided riots that occurred after Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. So unlike most other large cities, there was no destruction of the business community in Black districts and race relations did not deteriorate. The preservation of race relations and business communities helped expand business and home ownership opportunities for African Americans throughout the region. To the limited extent you see blight, it is primarily due changing economic conditions and more attractive malls and business parks.

Inspired by an Operation PUSH Expo and recalling Indianapolis’ heritage as home of the Negro Business League, Black Expo was founded here in 1970 and sparked the creation of similar Black Expos nationwide. Indianapolis merged with its surrounding county, which on the “Pro” side negated the financial effects of White Flight. On the “Con” side, it diluted urban voting power. Hence, the first black U.S. Congresswoman, Julia Carson, was elected in 1996. But Indianapolis has yet to elect a black mayor.