Emanuel AME Church, Charleston; (c) Soul Of America

Charleston History

Archeological digs of wooden huts indicate that Native Americans lived in Low Country near the coast for thousands of years before Christ. The comprised the Kiawah, Etiwan, Edisto, Stono and Wando and Ashepoo tribes whose names fittingly adorn sub-regions in greater Charleston. Within the region Europeans founded Charles Towne for England in 1670, at the tip of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers.

Central to the founding of this peninsula city was slavery, and for years Charleston was the largest American port trafficking slaves. In fact, slaves greatly outnumbered their slave masters, which was always a matter of concern to European Americans. Case in point, a major slave revolt led by a slave named Jemy began just outside Charleston in September 1739. In his brief, unsuccessful southern trek, Jemy freed slaves and killed slaveholders as the group headed towards Spanish-held St. Augustine, Florida.

Accepting the risks of occasional small uprisings against slavery, Charleston’s wheel of commerce spun ever so tightly around the obscene profits of slavery-enabled imports and exports. Such huge profits were worth the risks. Despite Charleston’s greater exposure to the annual impact of hurricanes, only a handful of colonial southern cities controlled by the British, Spanish or French, such as Norfolk, Savannah, Mobile and New Orleans, could compete with the excellent harbor resources and Caribbean proximity of Charleston. Though the American Revolution of the 1770s stimulated European immigration, African slaves were over half the population in South Carolina. Most African Americans from South Carolina who fought in the Revolutionary War were slaves fighting, in some cases, on both the American and British sides.

The lure for an escaped slave when they joined the British was instant and acknowledged freedom. The lure for slaves who joined the American Patriots with their master’s permission, was “hoped for freedom” after the war. Charleston was not a place for British celebrations during the war, as they were rudely defeated in several battles for the region. Even with a change of flags and freedom granted to courageous Black soldiers after the Revolutionary War, Charleston’s slave economy was soon humming with efficiency.

While slavery was always a horror for the enslaved and their families, there were geographical, skill and timing factors that adjusted the degree of inhumanity felt by a Black individual. By and large, Charleston White-to-Black relations were not as restrictive prior to 1822.

Unlike African Americans in other parts of South Carolina, who relentlessly toiled in rice and indigo fields, in Charleston they worked dignified jobs as longshoremen, shopkeepers, and trusted house servants. Some skilled slaves were even permitted to loan themselves out for extra income to be shared with their master. In such cases the enslaved person saved extra money to purchase freedom for himself or herself or a family member. African Americans developed their own dignified church-centered communities. Enslaved people could attend church with Free Persons of Color. Inevitably, a class system developed between freemen and slaves. Even in 1810, when free and enslaved African Americans comprised 53% of Charleston, the White Gentry-Poor Whites-Free Blacks-Black Slaves social hierarchy, in the larger sense, ran smoothly.

That all changed in 1822, when Denmark Vesey, an ex-slave who bought his freedom, began organizing 3,000 Black South Carolinians for an uprising against slavery. Vesey’s plan was ratted-out. He and his cohorts were executed. This well organized, large uprising attempt put politically powerful slaveholders on guard. They quickly passed a series of laws to restrict free blacks and black slaves, hired a lot more policemen, Black churches were banned and free persons of color over 15 had to pay a citizen tax. Teaching African Americans to read was banned, and free persons of color who left the USA could not return to South Carolina.

Downtown shop merchants and ship owners were determined to prevent potential interruption to their ill-gotten gains by issuing the Negro Seaman’s Act, which mandated that visiting black sailors be jailed when their ship set in port until their ship left. These laws remained in force until the end of the Civil War in 1865.

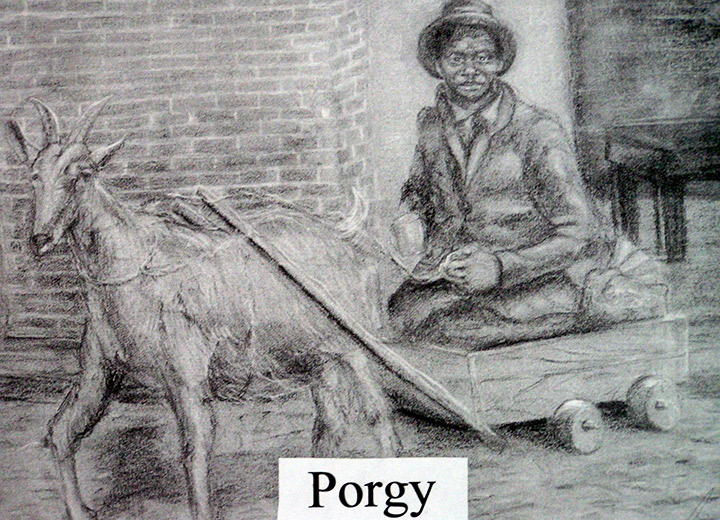

Portrait of the real Porgy; credit Soul Of America

In what could have been America’s finest declaration of human rights and reconciliation, General William T. Sherman of the Union Army issued Special Field Order 15 to begin the Reconstruction Era in 1865. This “40-acres and mule” order reserved Sea Islands off coastal South Carolina and Georgia for newly freed African Americans.

The Reconstruction Era was full of contradictions. Bishop Daniel Payne came to reestablish the AME church, which had been banned since the Denmark Vesey incident. Rev. Jonathan C. Gibbs of the Zion Presbyterian Church established the Zion school. The public school system in South Carolina was established, enabling many African Americans to begin a formal education. But before Special Field Order 15 could be broadly implemented, Andrew Johnson, who became President after Lincoln’s assassination, rescinded it and Union forces withdrew from the South. Emboldened by the change of events, the Klu Klux Klan rose throughout the South, exacting their special brand of hostilities. In 1867, Black riders had to stage ride-ins to protest being excluded from streetcars in Charleston. Ever more Black Codes were instituted to limit civil rights.

From the Antebellum South through the Civil Rights Movement, race matters would be a long divisive issue in South Carolina and the South in general. These matters caused many African Americans to leave a region they otherwise came to love, for less oppressive racism up North and West.

There are restored structures that date back to the 1700s, which maintain the city’s distinctive old-world charm and the African American presence is felt deep within it. Consistent with the population trends of today, African American residents are returning. More often than not, most middle-income Black folk are moving to and near North Charleston, since nearly all the prime properties are taken in Charleston or they just want more room.

It is taking years for the city and state to emerge from its erstwhile image and more race progress is required. For example, a proposal to erect a Vesey memorial in downtown Charleston sparked a firestorm of controversy. That reaction should not be surprising in the jewel of the slave-holding south. But don’t let an old-guard reaction stop you from visiting. The wheels of social progress are on an irreversible path forward in a city populated with Black politicians, despite the unfortunate shooting at Emmanuel AME Church. Perhaps the best progress proof-point is that African Americans are returning to live, work and retire. Lastly, a major slave museum is planned for the heart of Charleston.