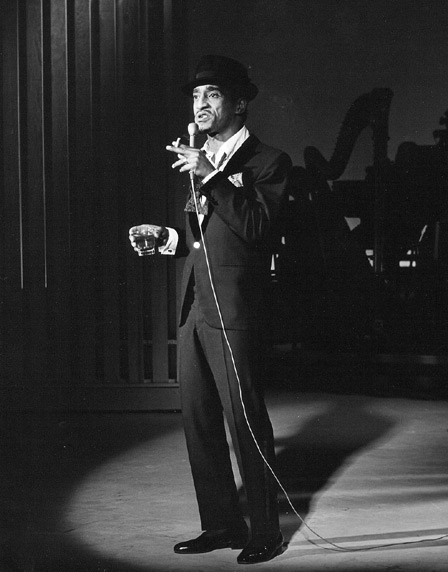

Sammy Davis, Jr. on The Strip

Sammy Integrates The Strip

Sam Davis Jr., aside from being the most talented entertainer in history, carries the distinction of opening doors in Las Vegas for all entertainers and ultimately, all people of color visiting Sin City.

A small number of African-Americans arrived after the Civil War and helped build Las Vegas. It remained peaceful, desegregated town for decades. Everything changed however, when construction of the Hoover Dam started in 1931. Hearing the call for work during the Great Depression, people of all stripes came to offer their labor. So did white segregationists from the South, who also brought Apartheid social standards to what had previously been a desegregated town.

A magnesium plant built for the Department of Defense 15 miles southeast of Las Vegas in Henderson, boosted black population from 180 to 3,000 between 1941-1944. Given increased competition for other jobs and social status, modest discrimination since 1931 transformed to most downtown casinos and clubs becoming “Whites Only.” As new casino resorts were built on the Strip, potential black patrons and employees could not set foot in them. A few downtown casinos remained accessible with small desegregated sections for slot machines.

With lower tax and more land for growth, casino resorts on The Strip soon outstripped those downtown. Hollywood and Broadway entertainers followed big money to the Strip’s fancy marquees. Sammy Davis, Jr. and his fellow members of the Will Maston Trio were the first black performing artists to play on the Strip in 1944 at El Rancho Motel & Casino. Though they helped fill the motel and casino, even the Trio could not stay as guests.

With the economy rebounding after 1945, more money found its way to Las Vegas. Casinos expanded on The Strip and Downtown. African Americans owning property downtown were pressured to move out and/or sell their property for less than market value. Jewish casino owners who catered to black patrons, moved just northwest of downtown. In 1947, four Jewish-owned, black-patron casinos opened on Jackson Street (Cotton Club, Ebony Club, Chickadee, Brown Derby) in the new black district.

Though Black entertainers nicknamed Las Vegas, “Mississippi of the West”, money was still bigger on The Strip. So Lena Horne played the Flamingo in 1947, Pearl Bailey played the El Rancho in 1948, Nat King Cole and Katherine Dunham played the El Rancho in 1951, just to name a few. They all stayed as guests in small cottages off the Strip or in the black boarding houses of West Las Vegas, which is northwest of downtown.

In April 1953, the Will Maston Trio featuring Sammy Davis, Jr. became the first black artists to headline a show on The Strip for the huge sum of $5,000/week. In 1954, Frank Sinatra invited Sammy to open his show down at the Sands. The trio was offered $7,500/week to headline at the Frontier on The Strip in November 1954. The Will Maston Trio featuring Sammy Davis, Jr. became the first African Americans offered complimentary room, board, drinks and access to a casino on The Strip at the Frontier. While recovering from an accident that took one of his eyes in November 1954, the Sands offered him $25,000 per week to perform with complimentary Sinatra-like accommodations.

The Moulin Rouge Casino & Hotel opened in the West Las Vegas in May 1955. Owned by Jewish Americans, it began with the premise of catering to back and and white patrons equally. Moulin Rouge was an immediate hit, drawing Sammy Davis, Jr., Harry Belafonte, Pearl Bailey, Nat King Cole, Louis Armstrong, Eartha Kitt and many more. So hot was its flame that Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Gregory Peck, Dorothy Lamour, Milton Berle and Jack Benny frequented the place after their gigs on The Strip. Trouble began when management started charging more per drink to African Americans to discourage blue-collar Black patrons. When word of this practice reached enough people, patronage declined. Others retaliated by reporting them to the gaming authorities. The casino soon lost its liquor license and by October 1955 the Moulin Rouge closed. Why would such a successful casino do such an obviously stupid thing to draw repudiation?

Though no one has proven it, the Moulin Rouge downfall has the signature of mob forces in the 1950s. So the truth surrounding its closure is probably buried in the desert.

In 1958, Nevada Governor Grant Sawyer pushed for laws to integrate hotels and casinos. He established the Gaming Control Board to enforce professional management practices, regulations and conduct license background checks. Other than Sands and Frontier casino resorts, integration was resisted during the Golden Era of mob-controlled Vegas. Even in the late 1950s, if Ethel Waters, Lena Horne or Dorothy Dandridge so much as touched the swimming pool, the entertainer was whisked away, white patrons were evacuated and the pool was drained. After a quick scrubbing, it was refilled.

But racism was no math for the world’s greatest all-around entertainer. In 1959, Sammy Davis, Jr. and his fellow “Rat Packers”, Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop broke racial barriers while filming Ocean’s Eleven, though oddly, Sammy played the grabage collector.

Before and after their Copacabana Room shows at the Sands (site of today’s Venetian), the Rat Pack visited casino crap tables all along The Strip. If a casino resort would not let Sammy in, Sinatra told them we’re not coming in. Given all the press the Rat Pack was generating worldwide before the film’s release, no casino resort wanted to be photographed turning away Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop at the height of their powers. Casinos relented and Sammy became a guest. Sinatra and Sammy also did several Copacabana acts poking fun at segregation. Sinatra, who was loved by, if not connected to the mob, enabled them to get away with it and he convinced many in the Hollywood community to take a similar stand for integration of The Strip and Hollywood. That breakthrough by Sammy Davis, Jr. became a proofppint that casinos would not lose money by having black guests. That would be valuable for civil rights legislation to come.

In 1960, federal and state authorities were putting pressure on the mob to clean up their act. The NAACP joined in by sponsoring a successful civil rights event at the Moulin Rouge in 26 March 1960 to desegregate casino resorts and hotels. Their focus was the Strip, since smaller casinos would follow their lead. With the 1960s Civil Rights Movement gaining momentum and publicity, national publications began mentioning Las Vegas segregation in the same breath as Southern segregation. With so much federal, state, media, entertainment and NAACP pressure, even the most ardent casino owners knew it was time to start letting African Americans into controlled areas of the casinos, lounges, restrooms and eventually, dining areas and rooms. By the mid-1960s, a few more casino resorts desegregated, enabling people of color to get jobs as card dealers.

In 1971, discrimination in hotels and casinos was officially ended by Nevada statute.

With racial barriers removed before his death, Las Vegas came to honor him. Sammy Davis, Jr., Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley became the crown princes of Las Vegas entertainment. When Sammy died in May 1990, he was accorded the ultimate Las Vegas tribute – they turned out the lights on The Strip for a minute in his honor. The same royal treatment was accorded Elvis Presley and Frank Sinatra.

Don Barden became the first African American to own a Las Vegas Casino. A Detroit native who earned his fortune in radio, cable TV, casinos and real estate, Barden is well respected for his business acumen. Hopes are high concerning his ability to transform the stodgy Fitzgerald Casino & Hotel downtown into a visitor magnet with soul.

Who wrote the article and in what year?

Thomas Dorsey, some time ago.