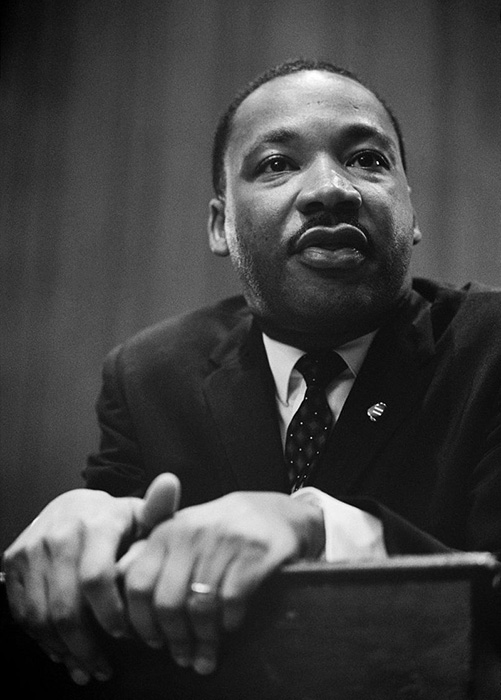

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

The Last Days of MLK

The Last Days of MLK must always punctuate the annals of American history, injustice and periodic triumph. For in death, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. achieved more human and labor rights breakthroughs than he could in life. His posthumous civil and labor rights achievement was a lightening rod that spread to other municipalities of the South, rooting out Jim Crow in months and years, that otherwise would have taken years and decades.

Though Dr. King is the largest icon of the Civil Rights Movement, other key parties involved in the events surrounding his death in Memphis were Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, Rev. Jesse Jackson, Memphis Mayor Henry Loeb, Memphis City Council, Memphis Department of Public Works, American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), AFL-CIO, Memphis Minister’s Association, A. Philip Randolph Institute, NAACP, SCLC, FBI, U.S. Attorney General, U.S. Undersecretary of Labor, President Lyndon Johnson and Coretta Scott King.

One day in late January 1968, 21 African-American sanitation workers were sent home due to rainy weather. They only received two hours of show-up pay. Meanwhile their Anglo-American counterparts were permitted to remain the entire day without working, yet earning a full day’s wage. This civil and labor rights indignity along with reprisals against union activity were common practice in Memphis. It persisted because a 1966 court injunction prohibited city employees from striking and picketing.

Then on 1 February 1968 two black sanitation workers were killed when a packer blade on a truck accidentally activated.

Risks associated with the packer blade had been previously reported by sanitation workers, but ignored by city management. That event combined with the other grievances compelled the public workers union into action. After many attempts to resolve grievances with the Department of Public Works, on 12 February, 1,200 out of 1,300 public works laborers went on strike. Their official demands were for pay raises, overtime pay, union recognition, open check-off of union dues and improved safety conditions. Their unofficial demand, as the “I Am A Man” signs they wore attested, was for human dignity. Only 34 of the city’s 180 garbage trucks operated on the first day of the strike.

Sanitation Workers Strike, 1968; credit Memphis Press-Scimitar Archives/University of Memphis.

Despite the anti-strike court injunction, on 13 February sanitation workers marched to City Hall to attempt a peaceful resolution to their grievances. But in the days following, the mayor and city council would not agree to any demands by the sanitation workers, since they considered the strikers to be lawbreakers. The mayor hired 51 temporary workers and ordered police to supervise garbage pick-up. In response, the AFSCME urged the strikers on.

NAACP Memphis branch and union leaders organized a small boycott of downtown businesses until the strike ended, and a thousand sanitation workers held peaceful marches and sit-ins at City Hall. But on 23 February, policemen maced the peaceful marchers, which included children, women and ministers. In response, black leaders of all stripes joined the ministers to form COME (Community On the Move for Equality) and call for a general business boycott, until the strike ends.

On 29 February, the mayor offered better pay, but without union recognition. So the union filed suit in federal court. In the weeks ahead, police arrested strikers and African-American students who participated in the march. On 14 March, Roy Wilkins of the NAACP and Bayard Rustin of the Asa Philip Randolph Institute addressed more than 10,000 people at Mason Temple Church of God in Christ in support of peaceful protest.

On invitation, Dr. King addressed 17,000 Memphians at Mason Temple COGIC and calls for a citywide march to be held on 22 March. The march was deferred due to a record snow storm, while strike negotiations continued. On 27 March, SCLC leader Ralph Abernathy addressed a strikers rally at Mason Temple, as negotiations collapsed. The two sides were no longer meeting. During that time, Clayborn Temple AME Church became a focal point. As the closest and largest church near downtown, it was the site of many rallies, the principal march staging area and pastored by a white minister at the time.

On 28 March, Dr. King led a gathering of 15,000 people at Clayborn Temple who intended to conduct a non-violent march to City Hall. The gathering consisted of organized, marchers and many opportunistic youths, who had no affiliation with the objectives of the marchers. Dr. King slowly led the procession across Hernando Street, then made a left on Beale Street, continuing up to Main Street where he made a right, heading towards City Hall. But only 7 blocks and 25 minutes into the march, disgruntled youths shattered windows, looted Beale Street merchants and clashed with police. During the ensuing melee, Dr. King and organized marchers were persuaded to return home or to Clayborn Temple for their own safety.

The day saw 280 arrests, 60 injured and one youth shot before 4,000 National Guardsmen moved in. It would be years before commerce on Beale Street recovered. It was the lowest point of Dr. King’s leadership in the Civil Rights Movement. He had never led a march where its organizers were loosely associated with others responsible for triggering violence. Consequently, Dr. King returned to Atlanta that day with his leadership reputation severely tarnished.

On 29 March, 300 sanitation workers and ministers, escorted by armored personnel carriers, marched peacefully from Clayborn Temple to City Hall. President Lyndon Johnson and AFL-CIO president George Meany offered assistance to resolve the dispute, but were both rejected by Memphis Mayor Loeb.

From 1966-1968, Dr. King’s reputation as a national leader able to get results was declining. Old Jim Crow practices proved resilient against Civil Rights legislation and peaceful SCLC demonstrations. Some black human rights organizations believed that non-violent principles were outdated, so they jockeyed to fill what they perceived as a leadership vacuum. Some other black-led organizations and the white establishment who once embraced his non-violent principles, perceived Dr. King as leading Negroes astray with “Stop The Vietnam War” rhetoric.

Concerned that he needed to restore his reputation as an effective non-violent leader, on 31 March, Dr. King canceled his trip to Africa to lead another peaceful Memphis march in hopes that it would reopen negotiations.

Upon return to Memphis on 3 April, Dr. King faced an injunction by city officials preventing him from leading another march, because they thought it would trigger violence. That night he delivered what Dr. Michael Eric Dyson and others describe as his greatest speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”. For one brief moment at Mason Temple, Dr. King pierced through the prism of the future, foreseeing his own death and our progress towards social equality. His closest associates say he had no wish to be a martyr, but in that final perfect speech he preached the fear of death out of himself.

Early morning 4 April 1968 SCLC lawyers got the injunction against King overturned. Dr. King heard the good news, but strangely remained in a somber mood. King, Abernathy, Young and Jackson spent the day strategizing Later that day, he and several associates were planning to leave the Lorraine Motel to meet with march organizers. King washed and dressed for dinner. King walked out of Room 306 onto the 2nd floor balcony of the Lorraine Hotel to take in the evening air.

As Time magazine reported, leaning casually on the green iron railing he chatted with his co-workers readying his Cadillac in the dusk below. To singer Ben Branch below, who was to perform at a Claiborne Temple rally later that evening, Dr. King made a special request, “I want you to sing that song Precious Lord for me — sing it real pretty.” Then Baruch said, “O.K., I will.”

Lorraine Motel balcony, Memphis

A heartbeat later at 6:01pm Central Standard Time, Dr. King was mortally wounded by a single rifle shot from a building across Mulberry Street. Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young and Jesse Jackson rushed to the side of their fallen leader, even as they pointed at the direction of the gun shot. Though he had a pulse when they took him to St. Joseph’s Hospital, 39-year old Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was pronounced dead at 7:05pm.

On 5 April, federal troops arrived, President Johnson sent the US Attorney General to Memphis and pressured the FBI to conduct an international manhunt for the killer. To his credit, President Johnson also assigned U.S. Undersecretary of Labor James Reynolds, to mediate the strike settlement. On 8 April, Coretta Scott King led dozens of national figures in a peaceful memorial march through downtown to Memphis City Hall in tribute to Dr. King. With Undersecretary Reynolds turning up the heat, on 16 April 1968, AFSCME leaders announced an agreement had been reached. Union members ratify it. Ralph Abernathy described the agreement as a “Significant and just breakthrough for labor and unions in the South”.

Despite riots around the nation, Dr. King’s reputation was elevated to martyrdom as the symbol of America’s Civil Rights Movement. He achieved posthumously more than he ever could in life. All over the nation, municipalities called on the memory of the Dr. King, “The Drum Major for Peace”, as they finally began implementing Civil Rights legislation in deed, not just law. That is when many boulevards nationwide were renamed in his honor.

The tale of Dr. King’s assassination does not close neatly. For many years thoughtful, but legally powerless Americans questioned how James Earl Ray, an escaped convict of limited intelligence and even less money, could singularly perpetrate the assassination, escape to two cities in Europe until capture in June 1968 with an unexplainably large amount of money in his possession, then be quickly convicted as the sole assassin without an accomplice(s).

Access to FBI documents after the 1993 Freedom of Information Act reveals much of what was hidden from government officials and the media for 25 years. Official documents having the signature of the FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover reveal that he instructed FBI agents to publicly and privately destroy the reputation and influence of Dr. King using a variety of illegal and immoral means. Those were wiretaps, tampered voice-over recordings to imply that Dr. King was a sex addict, paid informants, false mailings to the media, wrongfully branding him a communist, and tracking his every move without just cause.

Moreover, Hoover did nothing to ensure Dr. King’s safety despite repeated evidence from wiretaps and tracking, that certain parties had the motivation and means to assassinate him. Police that normally surrounded his hotel when in Memphis were inexplicably pulled away that fateful day. Though it happened in Memphis, his assassination could have been anywhere in America.

Broader implications of J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI directive, even if unintentional, have recently emerged. One FBI agent is linked to having knowledge of critical events surrounding James Earl Ray just prior to the assassination. After several meetings with James Earl Ray, new evidence and testimony, the King Family believed that others were involved in Dr. King’s assassination. For concerned citizens however, there is incontrovertible evidence that treatment of Dr. King was one of the most unlawful episodes ever committed by America’s top law enforcement officer — the dastardly J. Edgar Hoover who deserves part of the blame for the 1968 riots that engulfed America.

President Reagan signs bill to create MLK National Holiday in 1983

There is insufficient evidence to pinpoint James Earl Ray’s assistants or handlers, nor can we adequately characterize the FBI’s complete role in this sordid matter. But a taste of retribution came in 1983. The federal holiday bill honoring Dr. King passed the U.S. House of Representatives by a veto-proof count of 338 to 90. When President Reagan signed the bill in November 1983, it officially restored the good name of Dr. King.

Another taste of retribution came in 1999, when Coretta Scott King was alive. The King Family vs. Jowers and Other Unknown Co-Conspirators verdict had the jury conclude that there was a conspiracy in the assassination of Dr. King.