Los Angeles History

Biddy Mason Memorial in downtown Los Angeles

Los Angeles’ first Black newspaper, California Eagle, carried across the country by train porters, encouraged African-Americans to move here for a better life. Hearing the call between 1870 and 1910, African-American population grew from 100 to 7,500. During this time, Biddy Mason, founder of the first surviving African American church in Los Angeles, landowner and prosperous businesswoman, made her famous cross-country journey to Los Angeles. White segregationists from the South also came. The escalated and groomed discriminatory practices among the white population at large, to view people of color as 2nd class citizens. Also remember that no American woman could vote until 1922.

Though small in number, black leaders formed the Los Angeles Forum to help newcomers deal with new housing covenants that restricted access to parts of town and local Klu Klux Klan activity. African-Americans also entered politics. Frederick Roberts became the first African-American in the California State Assembly, serving from 1919 to 1933. Though Jewish-Americans faced significant discrimination in America, it was notably reduced in Los Angeles because Jewish entrepreneurs pioneered Hollywood movie studios. As Hollywood grew from hundreds of employees in the 1910s, to thousands of employees by the 1920s and most movie stars being Jewish, it produced clout that kept doors open for Jewish Americans.

As housing discrimination for people of color took root, African-Americans created a business district along Central Avenue. In the 1930s-40s, jazz thrived there. Artists and movie stars such as Nat King Cole, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Count Basie and Dexter Gordon could be found playing at the Dunbar Hotel on Central Avenue.

When world War II began on 7 December 1941, military discrimination restricted the number of African-American, Latino-American, Native-Americans and Asian-Americans who could join, limited the positions they could serve (Cook or Valet was common) and segregated their units. By default, such descrimination required a larger percentage of Anglo-American males to serve in forward battle positions. Such exclusion permitted people of color and Anglo-American females to flourish in munitions and aircraft manufacturing plants of Los Angeles. Since these jobs paid more than typical government jobs, they became the middleclass foundation of black Angelenos.

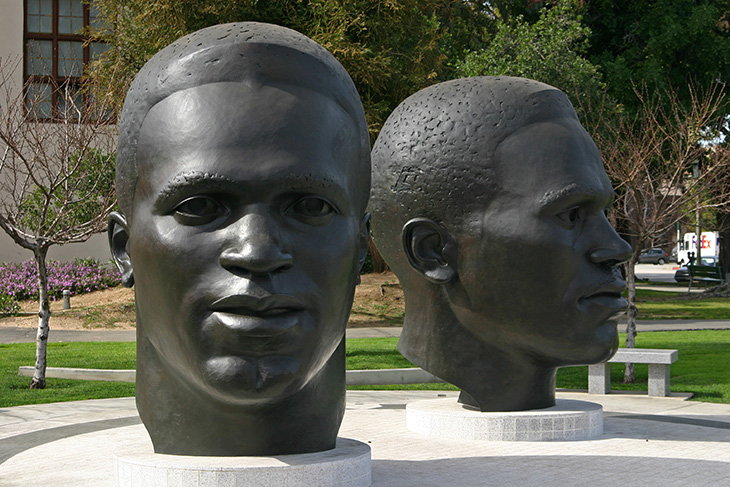

At this point, lets reflect upon Jackie Robinson and his brother Mack, raised in nearby Pasadena. Jackie attended Pasadena Junior College before attending UCLA for three years. Mack also received a college degree, but was underemployed due to racial discrimination. Scholarly Jackie also earned 24 letters in football, basketball, baseball and track. In football, he gained 12 yards a carry and led the nation in punt returns in 1939. In basketball, he led the Pacific Coast League in scoring two years and was league MVP.

Jackie & Mack Robinson Monument, Pasadena

Jackie played baseball for the Honolulu Bears in 1941 and served in the military during World War II as a college-degreed officer. In 1945, he played for the Kansas City Monarchs in the Negro National League with teammate Satchel Paige. It was widely rumored in Negro League Baseball that Major League Baseball would start its own Negro League as a precursor to integrated baseball years down the road. Negro League stars thought bigger paydays were imminent.

In a surprise move the Brooklyn Dodgers owner, Branch Rickey, signed Jackie to a contract in late 1945. Only Jackie had the perfect combination of a college education, great talent and calm temperament to avoid responding to N-word sleights, all necessary to break the color barrier for more Negro League players to follow. Since Canada never had the same degree of race problems as America, Jackie was first sent to the Dodgers’ Montreal Royals farm team, where he shifted from Shortstop to Second Baseman in preparation for Major League Baseball.

In 1946, Jackie married Rachel Issum and played in the Dodgers’ Daytona Beach farm team. In 1947, he finally entered Major League Baseball as a Dodger and won the Rookie of the Year Award. Jackie also won the National League MVP Award in 1949.

In his Hall of Fame career as a Brooklyn Dodger (1947-1956), Jackie batted .311, hit 137 home runs, had 734 runs batted in and stole 197 bases, including home plate several times. He helped the Dodgers win 6 National League pennants and in 1955, a world championship. Though Joe Louis was the first black man loved by all races in America. But Jackie Robinson (1919-1972) was the first black man to demonstrate that he could helped make white teammates champions.

Before Jackie Robinson died, his success on the field and vocal eloquence off the field help European Americans get comfortable hiring African Americans into interracial teamwork environments. He retired just before the Brooklyn Dodgers moved to Los Angeles in 1957. The City of Pasadena has a monument to Jackie & Mack Robinson in front of its city hall.

First AME Church entrance, Los Angeles

After World War II ended in 1945, job discrimination in aircraft plants resumed and housing discrimination amplified. It was so restrictive that by 1955, only Nat King Cole, who had a national TV show and was the biggest black celebrity of his era, was permitted to live in Hancock Park. Other people of color were not permitted to live or socialize west of Western Avenue. Other than dayworkers, butlers, chauffeurs and hotel workers, only Black and Latino stars like Hattie McDaniel, Ricardo Montalbán, Nat King Cole, Anthony Quinn, Lena Horne, Desi Arnaz, Sammy Davis Jr, Ella Fitzgerald, José Ferrer, Sam Cooke, Rita Moreno, Sidney Poitier, Dorothy Dandridge, Harry Belafonte and Katy Jurado would be seen at movie studios, Sunset Strip lounges and shops of Beverly Hills.

By 1960, African American population swelled to 450,000 and one prominent black architect, Paul R. Williams, gave the Beverly Hills Hotel its signature pink & green color and designed one of its best meeting areas. Such progress was deceptive however. As government reports would later prove, Los Angeles never job and housing discrimination the excluded African Americans from equal opportunity, nor did local officials address the rampant police profiling and brutality.

Though African-Americans escaped the Southern brand of extreme racial bigotry, in some ways it was worse for them. Many defense workers bought middleclass homes during WWII and the Korean War, but encountered oppressive job and housing discrimination and frequent police brutality. That stirred up vast resentment and pent up economic despair. Then in 1965, Watts District exploded when a police brutality event lit the fuse. As the first major riot during the modern Civil Rights Movement, it sparked national studies and caused many Americans of all stripes to reexamine the pace of racial progress.

In that political climate, a retired police officer and city councilman, Tom Bradley, became the first African American mayor of Los Angeles in 1973 and several African-Americans from California were elected to Congress.

During the 1970s and 1980s, Bradley opened city employment and contracts. Other public and private sector service jobs opened as well. Housing discrimination was greatly reduced. Bradley pushed for the building of the multi-million dollar Baldwin Hills-Crenshaw Mall. During his 20-year administration, Mayor Bradley oversaw an economic boom in the region. Despite noble efforts, economic prosperity in the form of blue-collar manufacturing jobs fled South and East LA. Much of the black middleclass, no longer constrained by housing discrimination and fed up with gang activity, moved to suburban communities like Long Beach, Carson, Pasadena, Moreno Valley and Riverside. But South-Central and parts of East Los Angeles became islands of economic depression. And under police chief Parker and the blue wall of silence, police brutality continued unabated.

In 1991, a year before the Rodney King Verdict there were peaceful protests at the courthouse downtown organized by First AME Church and Danny Bakewell, a civic activists. Their calm resolve targeted the hearing of a Korean American shop owner for the shooting death of Latasha Harlins. An edited version of the shop owner’s security videotape airing on local TV, indicated a brief skirmish at the counter, but did not indicate that the shop owner’s life was jeopardized or that Latasha was stealing anything.

The unedited version seen by fewer people, indicated that Latasha was acting in a suspicious manner. The shop owner thought she was about to steal something and verablly confronted Latasha asking her to leave without taking something. When Latasha approached the counter a brief skirmish ensued at the counter. Nothing in the videotape however, indicated that the shop owner’s life was in jeopardy or that Lasha had stolen anything. As Latasha turned towards the door, presumably to leave, the shop owner panicked and tragically, shot her.

The edited videotape repeated on local TV became larger than the single Manslaughter case it should have represented. In the black community, the Latasha Harlins Video put a face on systemic devaluation of black lives. When the judge’s decision convicted the shop-owner of Manslaughter, but sentenced her to Probation, it sent a racially-charged message throughout the black community. Black Life Is Not Valued.

If continued economic depression in South-Central created the gunpowder, that verdict created the fuse for riots that would follow later. With ongoing police profiling and brutality in the black community sanctioned by a police chief who openly defied Mayor Bradley and you could easily predict that the Rodney King Verdict would light the fuse.

The April 1992 riot began as an uprising based on indignation in South-Central LA. People threw trashcans and bottles as police cars raced out of the community. It quickly escalated into multi-racial conflagrations of African-Americans, Latino-Americans, Asian-Americans, and even Anglo-Americans. Each united in their sense of despair and wanton disregard for peace and property. Each divided in their sense of what represented solutions to the problem.

Despite lives lost and property damage, some good did occur that would have been impossible before the riot. Los Angeles got two subsequent black police chiefs. A major police profiling & brutality scandal was proven in the courts. Police are better trained to be sensitive to multicultural LA. Nearly all the burned out South-Central Los Angeles (renamed “South Los Angles”) businesses have been replaced. Some are better than before, including the intersection of Florence & Normandy where the 1992 Uprising started.

Even the Hip-Hop movement helped race relations by raising the blinds on urban culture to many suburbanites. Nevertheless, more progress in LA’s black community depends on improving the quality of education and getting more kids to graduation for trade school and college. Only then will the black community of South Los Angeles adapt to the Digital Age.