Frederick Douglass was born in Tuckahoe Creek, Maryland

Frederick Douglass in Maryland

Experience the spirit and determination of Frederick Douglass in Maryland. From 1818-1895, he was the great African-American abolitionist, orator, writer and statesman and a social trailblazer who married across race later in life. Born of Maryland, he was most influential African American of the 19th century. Douglass was the great agitator of the Anglo-American conscience concerning the horrors of slavery and social inequality. Visit Maryland and be inspired by the places where Frederick cultivated the will to fight and oratory gifts for the liberation of a people.

Enslaved by the Anthony Family, Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born around 1818 on Tuckahoe Creek in Talbot County, Maryland. The exact date is uncertain, but he later chose February 14 as his birthday. He was of a mixture of African, Native American and European. Frederick was named by his mother Harriet Bailey. After escaping to the North years later, he would drop his two middle names and take the surname Douglass.

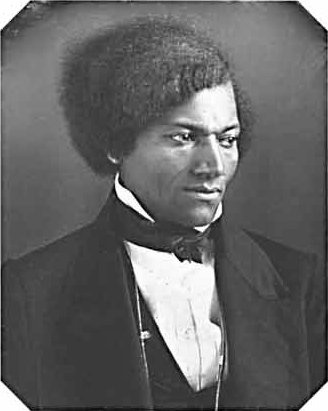

Frederick Douglass in 1848

Annapolis, a waterfront community with a rich sailing and seafood history, is an important stop in Douglass’ journey. This is where he gave two inspiring speeches—one at the Maryland State House and the other at the Mount Moriah A.M.E. Church (now the Banneker-Douglass Museum). You can visit these sites today to be immersed in Douglass’ heritage.

Maryland’s Eastern Shore, just a two-hour drive from Baltimore, is another key location in Douglass’ life. Made up of small towns dotted across a waterfront landscape, it’s not only where he was born, but it’s also where he persevered through many trials and tribulations. Visit the quaint shore towns of Easton and St. Michaels to walk where Frederick walked. Sit where he sat. And experience how Maryland helped shape the determination he used to forge his path to liberation.

After this early separation from his mother, young Frederick lived with his maternal grandmother, Betty Bailey. At the age of six, he was separated from his grandmother and moved to the Wye House plantation, where Aaron Anthony worked as overseer. After Anthony died, Douglass was given to Lucretia Auld, wife of Thomas Auld, who sent him to serve Thomas’ brother Hugh Auld in Baltimore.

When Douglass was about 12, Hugh Auld’s wife Sophia started teaching him the alphabet. Douglass described her as a tender hearted woman who treated him like a human being. Hugh Auld disapproved of the tutoring, feeling that literacy encouraged slaves to desire freedom. Under her husband’s influence one day, Sophia snatched a newspaper away from Douglass and ceased tutoring him. Douglass secretly continued to teach himself how to read and write. Douglass credited The Columbian Orator, an anthology that he discovered at age 12, with defining his views on freedom and human rights.

Frederick Douglass monument on the East Baltimore waterfront

In 1833, Thomas Auld took Frederick back from Hugh and sent him to work for Edward Covey, a poor farmer who had a reputation as a “slave-breaker.” He whipped Frederick regularly, and nearly broke him psychologically. In 1834, age 16 Frederick finally rebelled against the beatings and fought back. After Frederick won a physical confrontation, Covey never tried to beat him again.

In 1836, he tried to escape from Covey, but failed. In 1837, Douglass met and fell in love with Anna Murray, a free black woman in Baltimore about five years older than he. Her free status strengthened his belief in the possibility of gaining his own freedom. On September 3, 1838, Douglass successfully escaped by boarding a train to Northern cities.

After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became recognized as a national leader of the abolitionist movement in Massachusetts and New York due to his dazzling orator and influential writing. During his time, other abolitionists cited Douglass as a living counter-example to slaveholder arguments that people of African descent lacked intellectual capacity to function as independent American citizens. Prior to meeting him or reading his writings, most Anglo-American Northerners found it hard to believe that such a great orator and writer had been a slave.

Douglass bought a set of row houses in East Baltimore and wrote several autobiographies. He described his experience as a slave in the 1845 autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, which became a bestseller. The seminal work was influential in promoting the national cause of abolition, as was his second book, My Bondage and My Freedom in 1855.

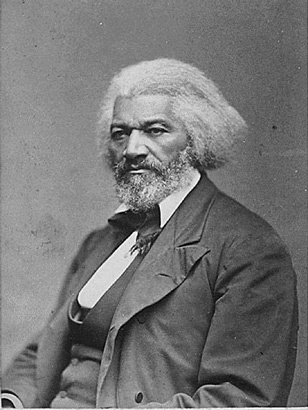

Frederick Douglass, older

Even today, Douglass is famous for at least two sayings. One example is when radical abolitionists, under the motto “No Union With Slaveholders”, criticized Douglass’ willingness to dialogue with slave owners, he famously replied: “I would unite with anybody to do right and with nobody to do wrong.” A second more famous saying from Douglas that is a unifying principle for civil activists is, “Power concedes nothing without struggle.”

After the Civil War, Douglass remained an active campaigner against slavery and wrote his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. First published in 1881 and revised in 1892, three years before his death, it covered events during and after the Civil War.

Source: http://www.hstc.org/museum-gardens/frederick-douglass

The journey starts here >> visitmaryland.org

When I read any article about Frederick Douglass, always remember his quote “Without a struggle, there can be no progress.”. One quote that i always remember when things don’t go my way.

Thank you for this.

Amen