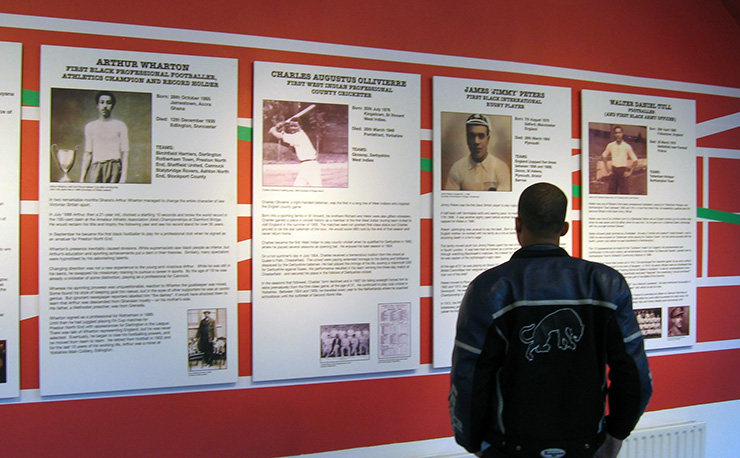

Historical figures exhibit in Black Cultural Archives, London

Black London History

Sandra Jackson-Opoku is an award-winning journalist, novelist, and travel writer. She is the author of the award-winning novel, The River Where Blood is Born and the bestselling Hot Johnny (and the Women Who Loved Him), both published by Ballantine/Randomhouse — Sandra Jackson-Opoku

If you’re looking for “Black London”, it’s not so hard to find. Its presence dates back to Roman Antiquity. African and Caribbean immigrants, their children, and children’s children are found everywhere from the Houses of Parliament to the halls of industry, the concert stages to the television screens, and out and about in public spaces. There are plenty of opportunities to experience it.

London is a pedestrian’s dream, one of the world’s most walkable, watchable cities. In warm weather, multitudes spill onto the streets, lingering at sidewalk cafes, biking through city parks, and jogging the promenades along the River Thames. Blacks move easily amongst them, giving special flavor to areas like Brixton, Peckham, and Ladbroke Grove with a variety of ethnic restaurants, open-air markets, entertainment venues, cultural centers, and Notting Hill Carnival — the biggest street festival in Europe.

That’s contemporary Black London for you. If you seek a more historic perspective, here’s where you might begin.

From Antiquity to the Elizabethan Era

The Romans invaded Britain in 43 AD. They built a trading settlement called Londinium on the northern banks of the River Thames. Among them were men like the Black Roman emperor, Septimius Severus, who ruled Britain from 208-211 AD, suppressing revolts and organizing reinforcements to the defensive wall around the city. A bust of Severus is displayed just inside the entrance to the British Museum. A full-length marble statue of the emperor in military dress (forearms broken à la Michelangelo’s David) is part of the museum’s Roman British collection.

Remnants of the London Wall are preserved at sites like Tower Hill, across from the Tower of London.

John Blanke was a 16th-century musician in the Tudor courts of Henry VII and Henry VIII. Two scenes from the Westminster Tournament Roll (a 500-year-old tapestry archived at the London College of Arms) depict him opulently attired and turbaned, riding a horse and playing the trumpet.

Blacks were also musicians, dancers, tradesmen, and ladies-in-waiting in Elizabethan England. There were so many around during a period of famine and social unrest that Queen Elizabeth I proclaimed, “those kinde of people should be sente forth of the land.” Her edict was largely ignored since no recompense was offered and people weren’t in a hurry to give up their slaves and servants, friends, and neighbors.

The black population did dwindle, though not necessarily from the queen’s decree. They were subject to the same perils as their peers. Medieval plagues decimated London’s population. Blacks also began disappearing through interbreeding; DNA investigation of a group of white British males indicates a rare genetic link to a community in West Africa. Thus, blackness lives on in the British blood.

Even as earlier populations were wiped out or absorbed, “those kind of people” would continue to arrive, and “that kind” of xenophobia would reoccur.

Central London

Central London includes some of the city’s innermost clusters of boroughs. Historic and modern attractions like the Houses of Parliament, Parliament Square, and Trafalgar Square each contain traces of a historic black presence.

The 1805 Battle of Trafalgar against the French and Spanish was Britain’s most famous naval victory. The HMS Victory’s crew was apparently multinational, per a fresco in the Royal Gallery of Parliament showing figures of two black sailors. One is tending to the wounded, the other pointing out a French sniper. Diane Abbott became the first black woman elected to British Parliament in 1987 and her portrait is also prominently displayed in the Parliamentary Art Collection.

Blackamoor was a term used to denote people of dark complexion or African descent. At the northeast corner of Trafalgar Square in St. Martin in the Fields Anglican Church, a woman identified only as “Margaret, a Moor” was buried in 1571.

The centerpiece of Trafalgar Square is Nelson’s Column, a monument to Admiral Horatio Nelson who died at the Battle of Trafalgar. At the foot of the column on the left, right next to the dying Nelson, is another image of a black sailor, this one wielding a rifle. The Square also features a towering bronze statue of Toussaint L’Ouverture, leader of the Haitian Revolution.

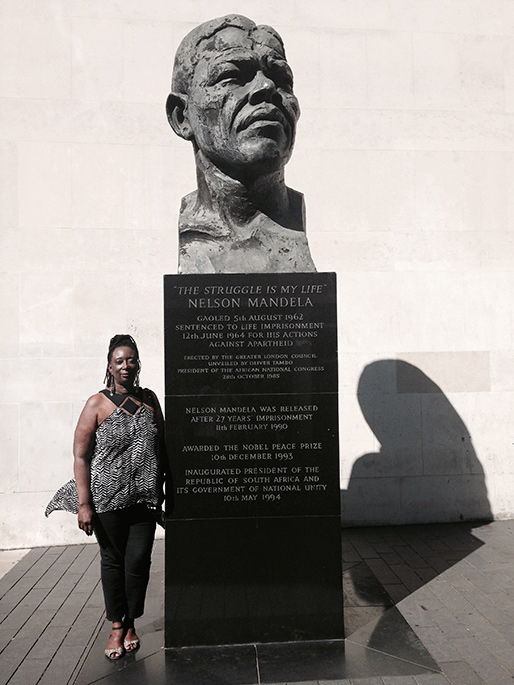

Although Nelson Mandela never lived in London, he visited the city during the height of ANC anti-apartheid campaigns in the 1960s, before his infamous 28-year imprisonment. Westminster’s Parliament Square features a bronze likeness of the South African leader, alongside “heroes” like Winston Churchill, Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, and several others who might be aghast at sharing a posthumous space with a black man. When Mandela passed away in 2013, Londoners flocked to Parliament Square to lay funeral wreaths and flowers at his statue.

Sandra Jackson-Opoku standing next Nelson Mandela Monument, London; credit Leslie Palmer

A black granite bust of Mandela is also located just outside of Central London near the upper level of the Royal Festival Hall at South Bank Centre, a massive arts and entertainment complex on the south bank of the River Thames. This was a replacement for an earlier sculpture vandalized by racist gangs in 1984.

While the legacies of Abbott, L’Ouverture, and Mandela are committed to the history, not much is known of others we’ve discovered. We can only acknowledge them as unsung characters in the story of Black London. The British National Archives offers an online virtual tour that maps the African and Asian presence in London and other of cities from 1500 to 1850.

Sugar, Slavery and the Sea

After Liverpool, London was Britain’s second largest seaport. Many a merchant’s fortunes were made from slaving and sugar profits.

Greenwich in Southeast London is known as the place where international time is set. It was once the site of a Victorian-era waterfront settlement of slaves, seaman, stevedores, black loyalists from the American Revolutionary War, barkeeps, and assorted hustlers of all races.

Greenwich now showcases The Royal Museums Greenwich, a World Heritage Site of historic landmarks including the National Maritime Museum, the Royal Observatory, the Queen’s House and the dry-docked Cutty Sark, one of the last great British clipper ships.

Each August the National Maritime Museum commemorates the anniversary of Britain’s abolition of the slave trade with a series of family-friendly events – music, workshops, talks, and tours about the transatlantic slave trade and the black contribution to the maritime industry.

The Museum of London Docklands is housed in a converted sugar warehouse on the Isle of Dogs in East London. The multimedia “London, Sugar, and Slavery” exhibit tells the story of how slavery shaped London’s economy from the 17th century onward.

Heritage Plaques

Stroll through nearly any London neighborhood and you’ll spot platter-sized ceramic plaques affixed to the facades of certain buildings. The English Heritage (EH) Blue Plaque Scheme marks the places where famous people lived or worked, or important events took place. Over its 150-year history, EH has recognized close to 900 figures, from Benjamin Franklin to Richard Burton, and Agatha Christie to Sigmund Freud.

One thing all EH honorees have in common is that they’ve been dead for at least 20 years, though all are not British. If fact, two non-native black musicians rank in the Top 10 Blue Plaques of London — Jimi Hendrix and Bob Marley — though a relative few honorees have been of African descent.

Activist, musician, and former model Jak Beula aims to change all that. His Nubian Jak (NJ) Heritage Plaque Scheme recognizes significant blacks and ethnic minorities at places associated with their legacies. NJ plaques number 15 and counting (see below for a partial listing).

African and Caribbean immigrants to England in the mid-20th century met severe discrimination in housing, employment, and outright violence. Expressing anti-immigrant sentiments, racist mobs (some gussied up like Edwardian dandies and calling themselves Teddy Boys) accosted blacks on the streets, beating them up and shouting “bye-bye, blackbird.”

When a young man named Kelso Cochrane was brutally stabbed in 1959, his murder galvanized the local black community. An NJ blue plaque at 36 Golborne Road in Kensington memorializes this moment.

Streets and Statues, Monuments and Memorials

Brixton, South London has absorbed more black settlers than anywhere in the city. A number of places reflect this heritage, from the bustling multicultural market at Brixton Village to Windrush Square, a heritage site named for the ship that brought the first large group of Caribbean people to London in 1948.

Windrush Square, London

The Square is also home to the Black Cultural Archives, the largest repository of information on blacks in Britain. Among its many holdings is an 1800-year old silver coin depicting Septimius Severus, Black Roman Emperor of London.

Jamaican pan-African leader Marcus Garvey lived here some years after his deportation from the U.S. No less than six places memorialize his presence: a street named Marcus Garvey Way in Brixton and the Marcus Garvey Library in North London’s Tottenham Green Leisure Centre. An EH blue plaque marks 53 Talgarth Road in Hammersmith as the place Garvey lived from 1934 and died in 1940. Marcus Garvey Park is located behind Hammersmith Road near Olympia. Yet another plaque is placed outside 2 Beaumont Crescent in West Kensington, where Garvey’s UNIA offices were located. There is also a statue of Garvey at Willesden Green Library in Brent.

Among the jobs open to immigrants in the 1950s were conductors, drivers, and subway staff in London Transport. There were labor shortages at the time and governmental representatives actually traveled to the Caribbean, recruiting employees and paying their fares to England. Housed in the old Flower Market at Covent Gardens, the London Transport Museum tells this history in the exhibit, “Generations: Celebrating 50 Years of Caribbean Recruitment.”

A collection of conceptual sculptures engraved with lines of poetry stands at Fen Court in London’s Financial District. “The Gilt of Cain, Victims of the Slave Trade Memorial” was unveiled and dedicated by Bishop Desmond Tutu on the bicentennial of Britain’s Abolition of the Slave Trade in 2007.

The Abolitionists

Black abolitionists, in fact, played a central role in the anti-slavery movement and the passing of the 1807 Abolition Act. The slave narrative was the literary voice for the movement, both in 19th century England and the U.S.

A fancy four-story house built of Bath stones stands at 19 Charles Street in Mayfair. At this address (though not the same structure) some 250 years ago, Ignatius Sancho — ex-slave, abolitionist, writer, and composer known as the first black to vote in a British election — ran a grocery store with his Caribbean wife, Ann Osborne. An NJ brown plaque at the nearby Foreign and Commonwealth Office commemorates this history. A Friends of Greenwich Park White Plaque is also placed at Montague House, where Sancho served as a butler to the Duke and Duchess of Montagu, and a Westminster Council (WC) Green Plaque marks his burial site at St. Margaret’s Church in Westminster.

Olaudah Equiano was another famous abolitionist who penned one of the first self-authored slave narratives. A WC Green Plaque is placed at his former address at 73 Riding House Street in Paddington.

Women also played a crucial role in the abolition movement. Mary Prince was a former Bermudan bondswoman whose 1929 slave narrative made her the first black British woman to be published in the UK. An NJ bronze heritage plaque on Senate House at the University of London in Bloomsbury is close to where Prince once lived.

Many Plaques, Many Colors

In addition to English Heritage (EH) and the Nubian Jak (NJ) Community Trust, some of the city’s boroughs and independent organizations have organized their own plaque schemes in shades of white, brown, green, blue, and bronze. Black plaques will not concern us here, as they do not recognize African heritage but murder, mayhem, and “memorials to misadventure.” The majority of commemorative plaques are placed on private property. Feel free to view them from the outside but don’t disturb the residents. These buildings are generally not open to the public. The following is a sampling of Black London plaques.

African National Congress London offices are located at 28 Penton Street in Islington where a Nubian Jak green plaque is mounted.

Ira Aldridge was a 19th century American-born actor. Londoners dubbed him “The African Roscius” (after the classic Roman actor, Quintus Roscius Gallus). An EH blue plaque marks his former dwelling at 5 Hamlet Road, Upper Norwood, Southeast London.

John Richard Archer, London’s first black mayor, served as Mayor of Battersea from 1913-1914. An NJ blue plaque is mounted at the photography shop where he lived and worked at 214 Battersea Park Road.

Sidney Bechet, the US jazz artist received an NJ blue plaque at his former home, 27 Conway Street, Fitzrovia, Central London.

Cetshwayo, the deposed 19th century Zulu King resided at 18 Melbury Road in Kensington and Chelsea, a spot marked by an EH blue plaque.

Sir Learie Nicholas Constantine, Trinidadian cricketer, author, lawyer, and statesman, was the first black to challenge (and win) a racial discrimination case in court. He was knighted in 1962, awarded a peerage in 1969 and became the first black to sit in the House of Lords. An EH blue plaque stands at his former home at 101 Lexham Gardens, Earl’s Court. An NJ blue plaque is mounted at Kendal Court in Camden, where he spent his last years.

Frederick Douglass, African-American abolitionist, author, orator, and statesman stayed at a house in Chelsea in 1846. An NJ blue plaque marks the address at 5 Whiteshead Grove.

Leslie Palmer is the only living legend to be honored with blue plaques. In 1973, Palmer pioneered the template for the modern Notting Hill Carnival, transforming a community carnival into an international event. Russell Henderson, who recently passed away at the age of 91, was a master steel drummer, credited in 1965, with taking a local neighborhood fair into the streets. NJ blue plaques at Carnival Square on Tavistock Road, Ladbroke Grove acknowledge their contributions.

Jimi Hendrix was the first rock star awarded an EH blue plaque, placed at 23 Brook Street in Mayfair, where he lived from 1968-1969. Plans are reportedly underway to transform the flat into a museum. The Cumberland Hotel near Marble Arch was his last known address and now has a special Jimi Hendrix memorial suite inside.

Leslie “Hutch” Hutchinson, the highest paid performer in Britain during the 1920s was a favorite singer of Edward, Prince of Wales. An EH blue plaque marks his former home at 31 Steele’s Road in Chalk Farm, Northwest London.

C.L.R. James was a Trinidadian writer, intellectual and activist. An NJ blue plaque is placed at 165 Railton Road, Brixton where he lived and died.

Bob Marley lived, recorded, and performed in London at several points during the 1970s. A Brent Council Blue Plaque at The Circle in Neasden, and an NJ blue plaque at 34 Ridgemont Gardens in Bloomsbury mark two of his former residences.

Kwame Nkrumah was the first president of Ghana. An EH blue plaque is affixed to the house where he lived from 1945-47 at 60 Burghley Road in Camden.

Paul Robeson was an African American performer and activist who worked in 1920s London as an actor. An EH blue plaque memorializes his former home at the Chestnuts, Branch Hill in Hampstead (now noted for having more millionaires than any place in the UK).

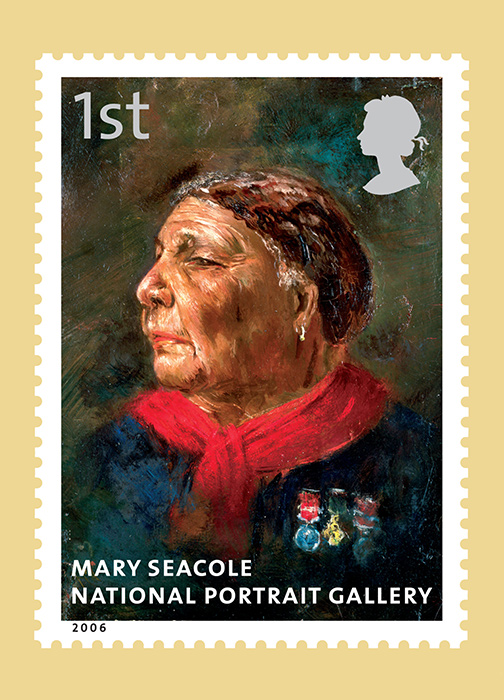

Mary Seacole portrait; credit Royal Mail special issue stamp #2006

Mary Seacole was a Jamaican nurse to the British Army during the Crimean War, where she became known as “The Black Florence Nightingale.” She later wrote memoirs of her travels, The Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands. Her home at 14 Soho Square in Westminster is graced with an EH blue plaque. An iconic 1869 painting of Seacole hangs in the National Portrait Gallery in Westminster. The image was reproduced this year as a special issue postage stamp and emblazoned on a postbox outside 10 Acre Lane in Brixton.